Research Interests and Projects

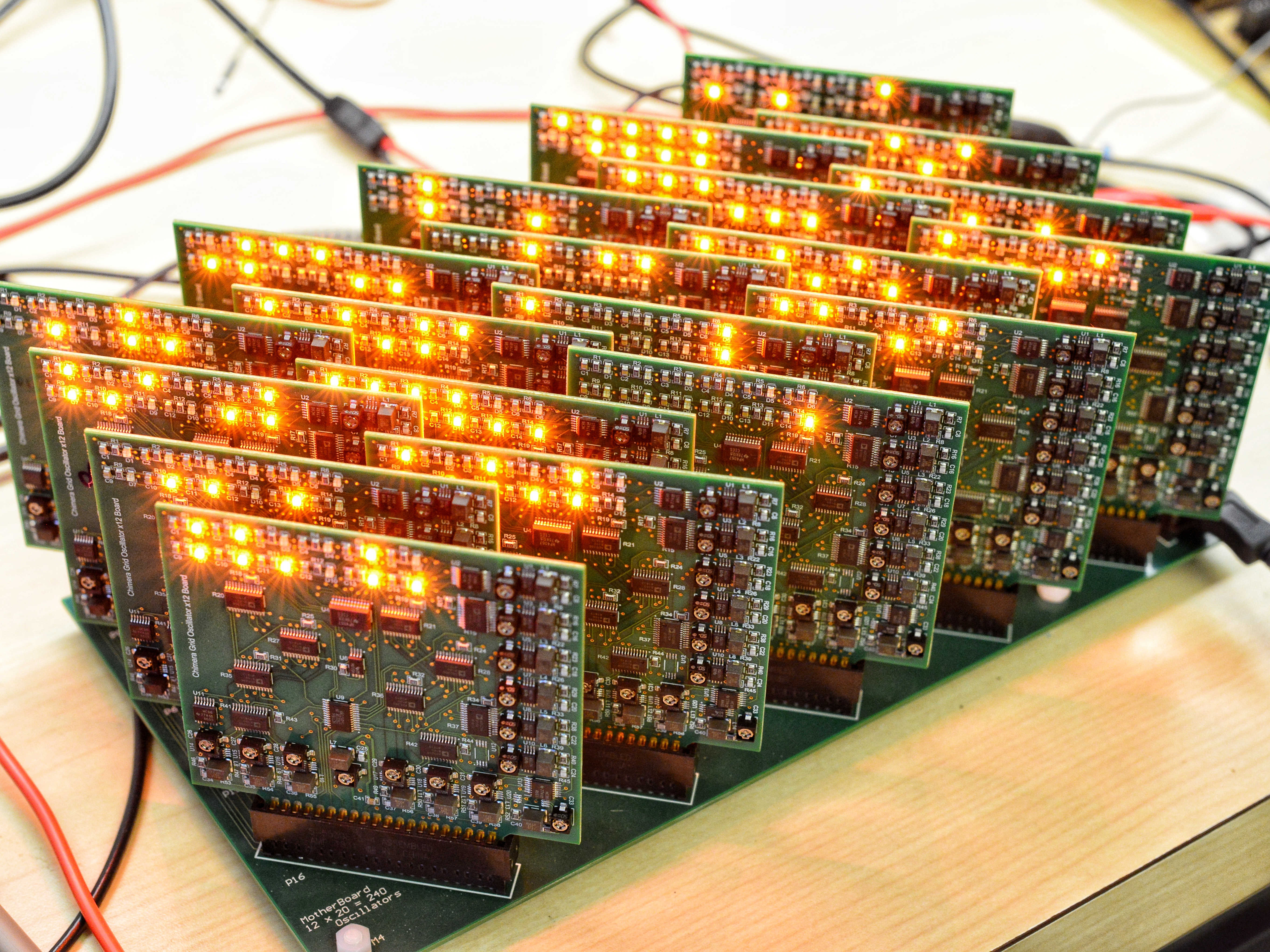

Oscillator-based von Neumann and non-von Neumann Computing

|

|

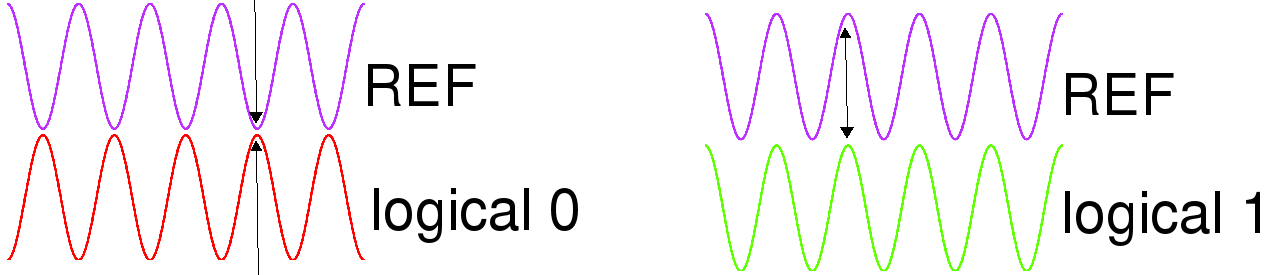

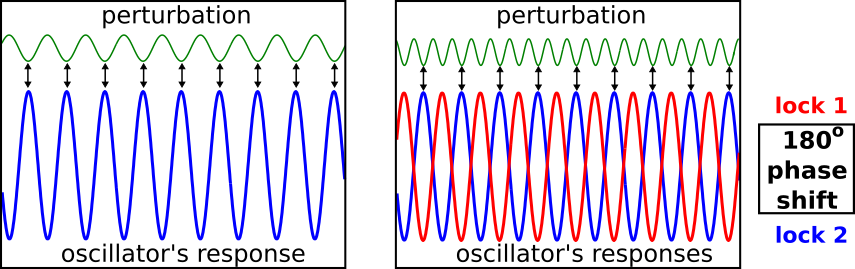

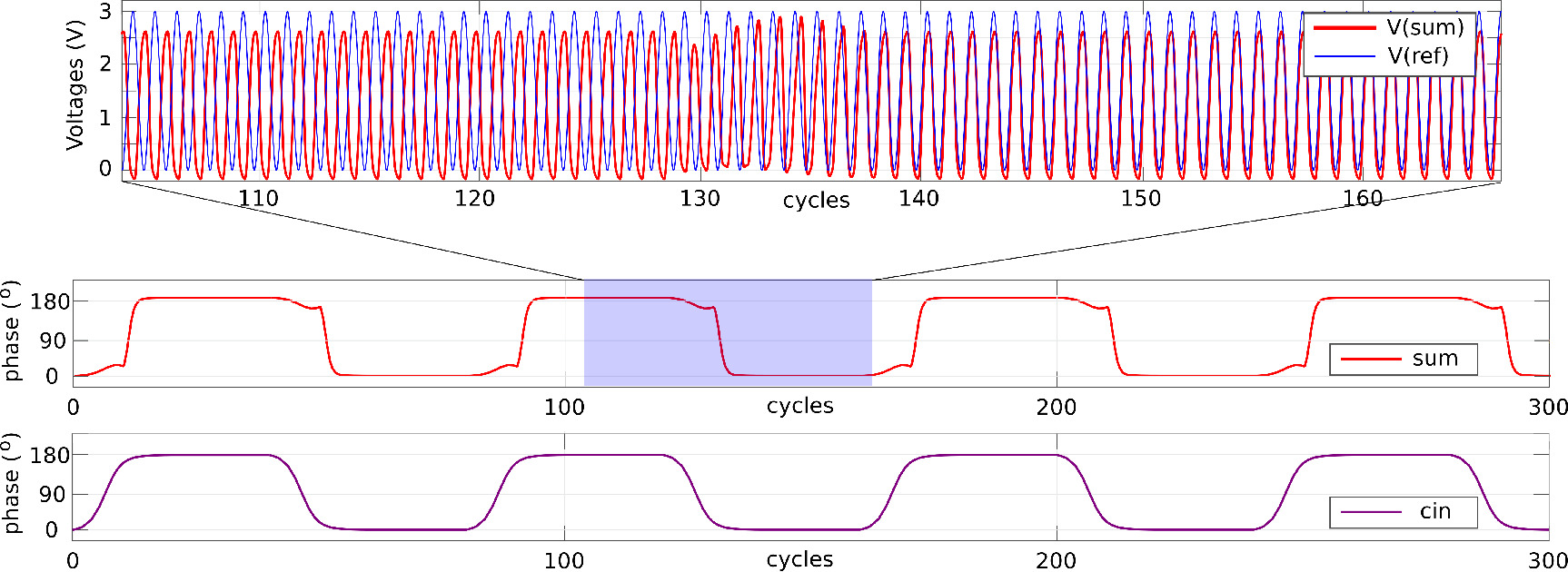

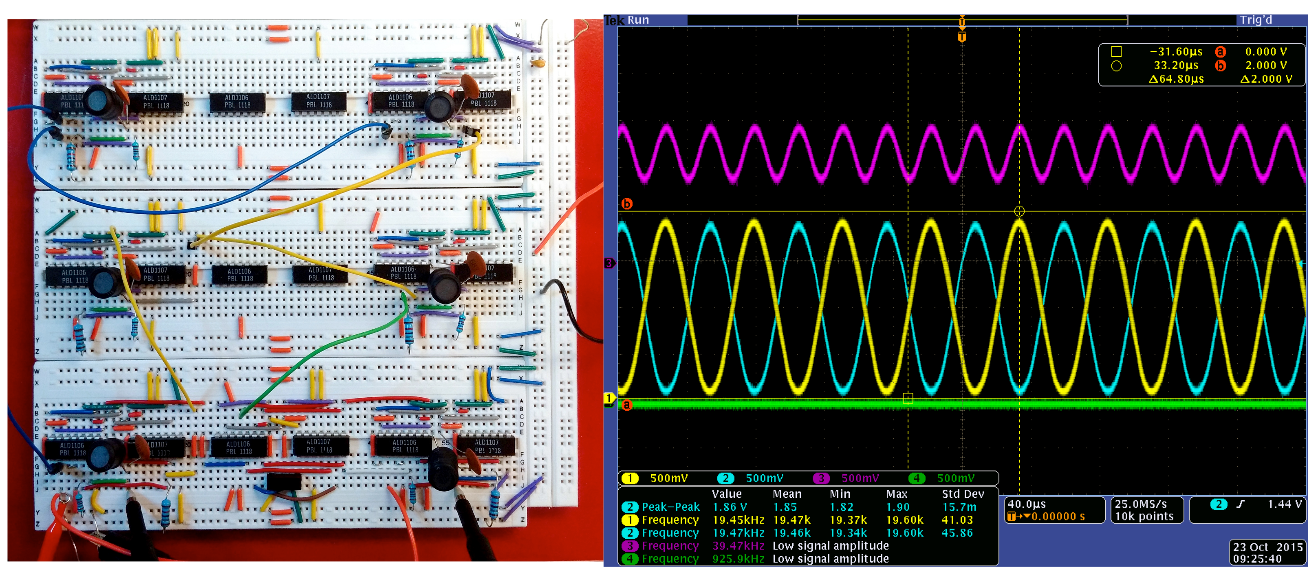

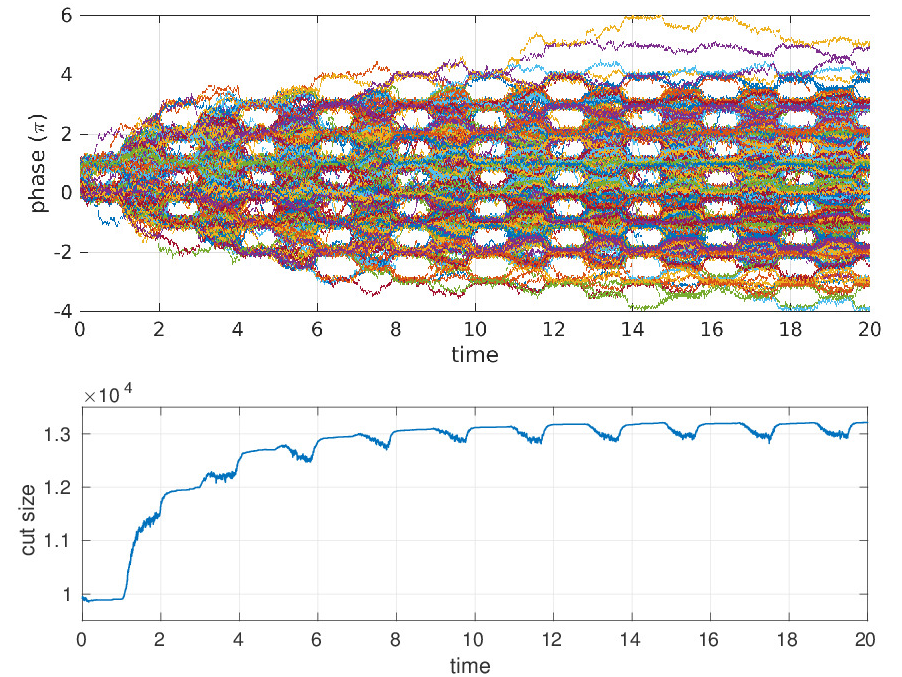

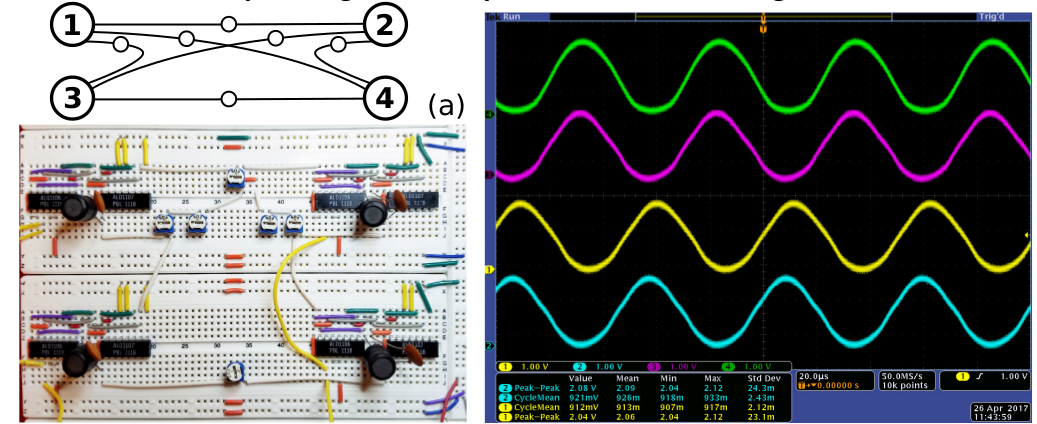

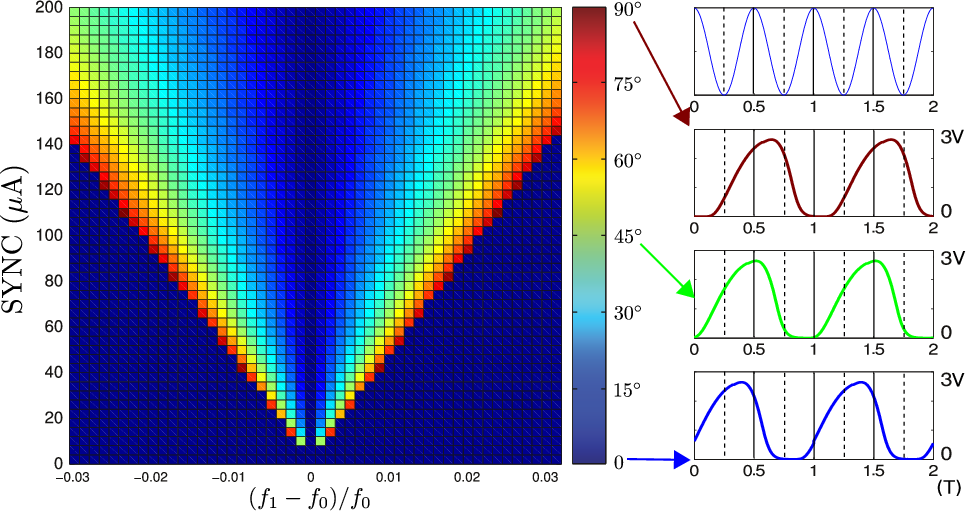

We aim to use oscillators to implement Ising machines as well general-purpose Boolean computation systems. In such systems, logic is encoded using the phase of oscillatory signals, rather than voltage levels. Such phase encoding has long been used in radio communication for its superior noise immunity; we show that it can also be used for computation, using self-sustaining nonlinear oscillators as underlying logic elements. \(\longleftarrow\) Illustration of the Ising model. |

|

The oscillators can be from any physical domain, including electrical (eg, using CMOS), biological (neurons, intracellular oscillators), nanotechnological (spin torque nano-oscillators, MEMS resonators), optical (lasers), etc.. Depending on the oscillator technology used, there is great potential for high-speed and low-power operation. \(\longleftarrow\) Phase lock under injection locking in mechanical metronomes — a key mechanism underlying our computation systems. We have developed the core theory and design tools for such systems; we have also realized proof-of-concept prototypes using CMOS technology, including both Finite State Machines (FSMs) for von Neumann architectures, and Ising machines for solving combinatorial optimization problems. We believe that oscillator-based Boolean computation systems, implemented with CMOS or other nanoscale devices from spintronics, MEMS, or silicon photonics, will emerge as a key next-generation technology for computing. |

▼ Click on the arrow to learn more

Device Compact Modelling

|

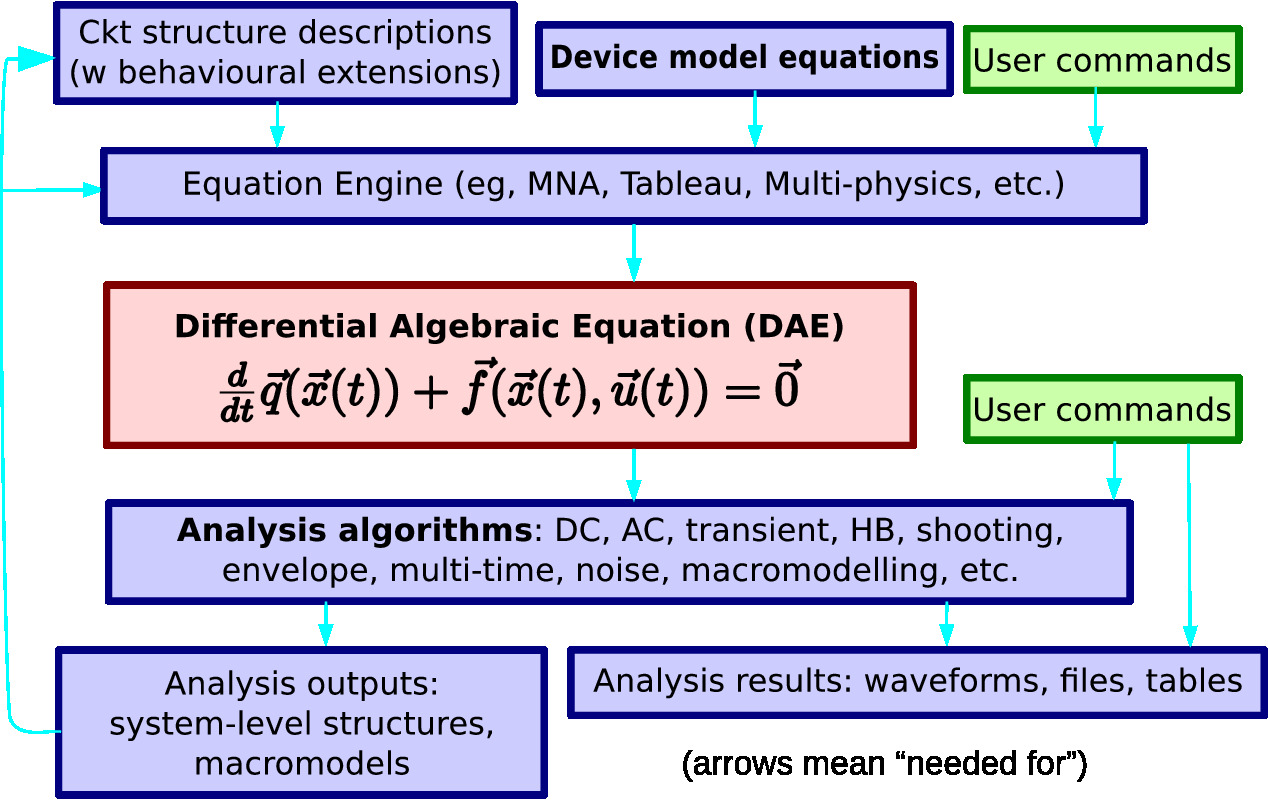

A long-standing barrier to research in models and algorithms for continuous-time simulation has been the lack of a powerful yet convenient platform for prototyping new ideas. To address this issue, we have developed the Model and Algorithm Prototyping Platform (MAPP). MAPP's modular structuring makes it possible to add a new device with only minimal knowledge of simulation algorithms; similarly, new simulation algorithms can be added easily, with little knowledge of the details of the devices in MAPP. MAPP has been released as open source on GitHub under the GNU Public License. |

|

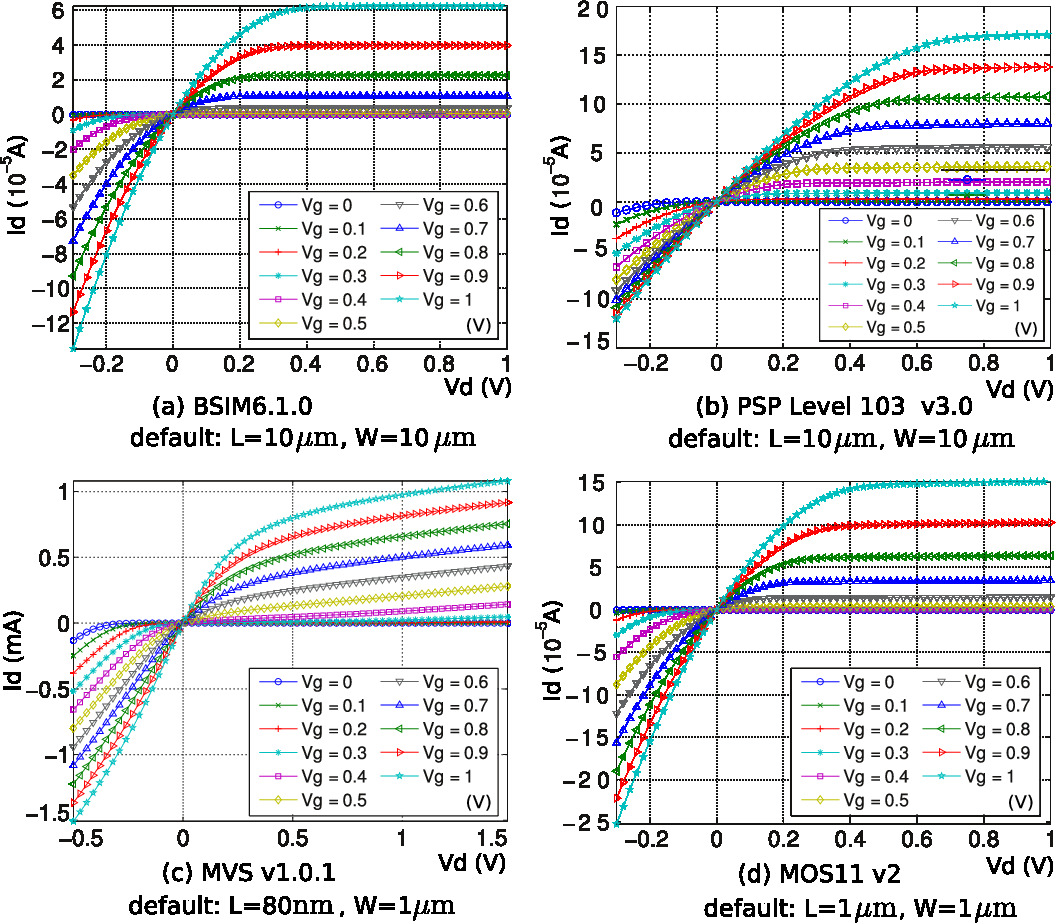

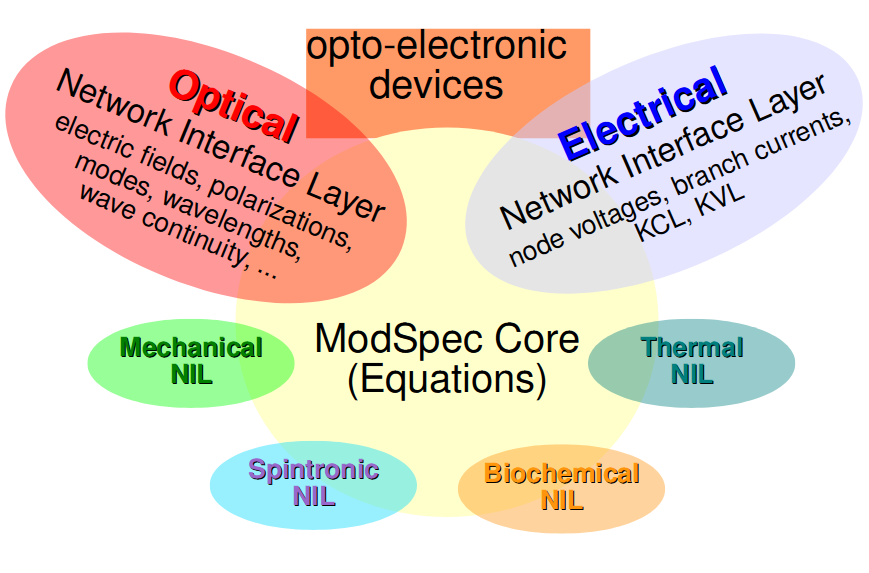

We have been able to prototype, test and debug many device compact models with the help of MAPP, including various models for MOSFETs (BSIM, PSP, MVS, MIT/Purdue Fe-FET models, resonate body transistor, etc.), optical devices (MIT ring resonator, Purdue micro-ring frequency comb, Berkeley VCSEL, etc.), spintronic devices (MTJ, piezomagnetic spin torque oscillator, etc.), and other devices (RRAM/memrisors, ESD clamps, magnetic cores, etc.). Device models in MAPP are specified in an executable format — ModSpec, which is designed to work with devices and systems from multiple physical domains, and is not limited to electrical circuits. |

|

|

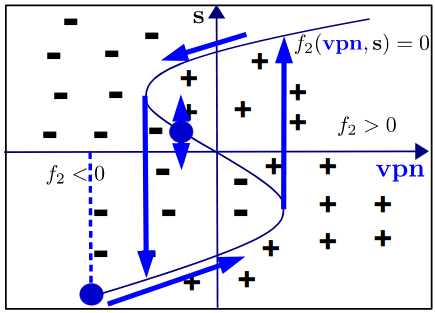

Existing models for memristors all suffer from problems associated with mathematical ill-posedness, thus do not work well in simulation, e.g., none generates usable DC operating points for circuit design. We have been able to identify the problem, show the proper way of modelling hysteresis using internal state variables, and provide proper implementations of the models in both ModSpec and Verilog-A (an industry-standard compact modelling language). The result is BMM — a collection of well-posed memristor models. Furthermore, the general formalism for modelling hysteresis can be applied to ESD protection devices as well. BESD is a collection of models that use only smooth and continuous functions to capture the ESD snapback phenomenon, which previously required the use of if-else statements and often caused convergence problems. |

|

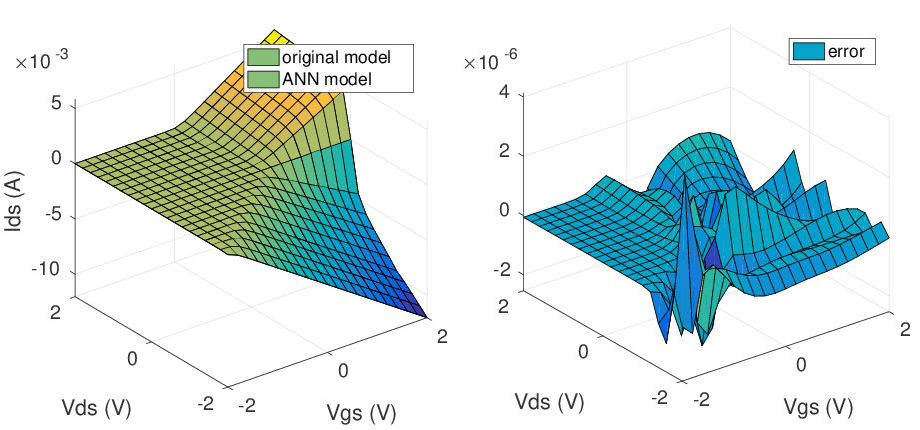

Handcrafting device compact models takes manpower and requires expertise in device physics, numerical analysis, and the code structure of specific simulators. Therefore, it is often not a feasible option if one wants to deploy new devices quickly. We have been able to develop several types of automatic compact model generation techniques, utilizing spline interpolations, Chebyshev expansions, and artificial neural networks (ANNs). Not only can we automate the modelling process, the resulting table-based and ANN-based models can also offer significant speedup and markedly improved numerical properties such as smoothness and differentiability over the corresponding handcrafted compact models. |

Advanced Simulation Algorithms

|

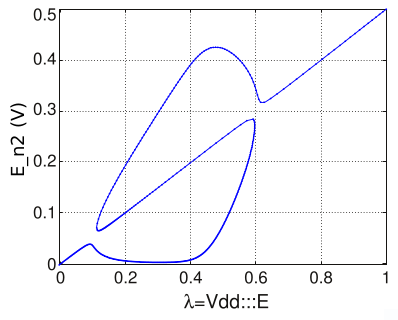

We have been able to prototype many simulation algorithms with the help of MAPP, including common analyses like DC, AC, transient (time integration), DC sensitivity, etc., and more advanced ones like homotopy (arc-length continuation method), shooting, Harmonic Balance (including multi-tone), transient sensitivity, phase-macromodel-based analyses, Stochastic Steady State and Stochastic AC analyses, polynomial-chaos-based uncertainty quantification, etc.. We have also designed SPICE-compatible initialization and limiting schemes as convergence aids that can fit in the differential equation formulation. |

|

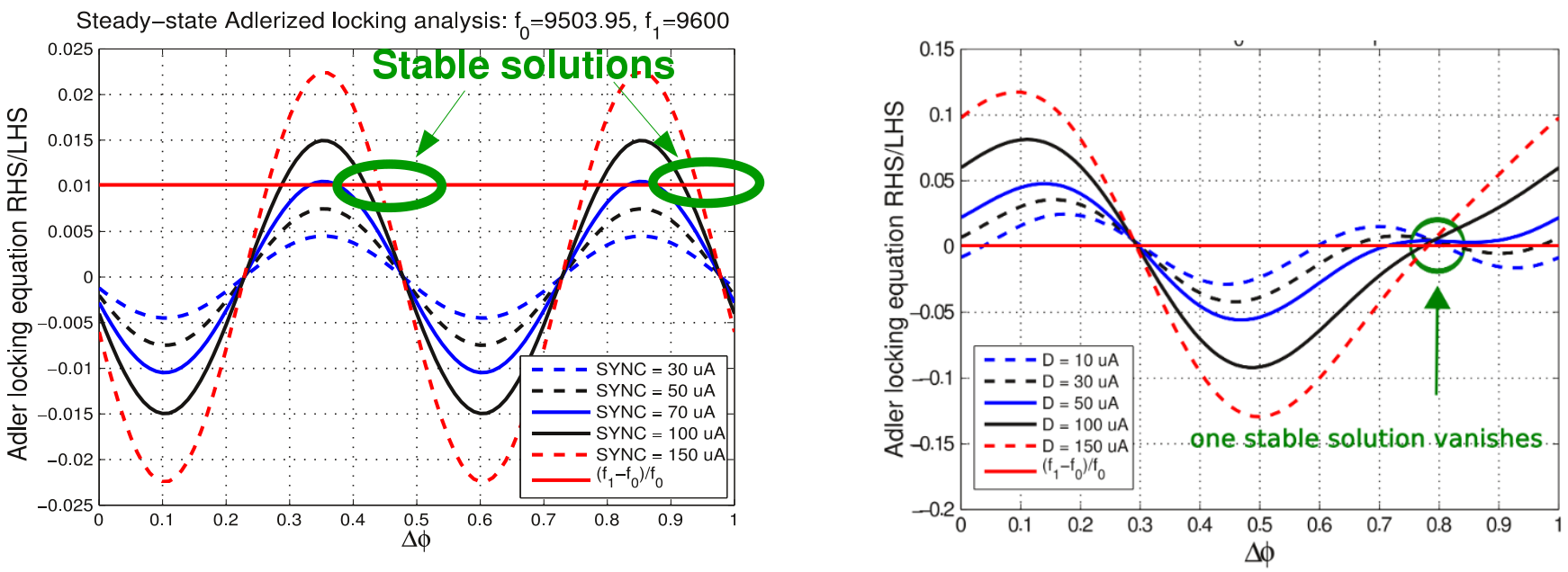

Among them, several analyses are essential for our research in oscillator-based computation. Periodic Steady State (PSS) techniques such as shooting and Harmonic Balance are the foundation of oscillator analysis; PPV-based phase macromodels and GenAdler-based analyses are crucial for analyzing injection locking properties and for speeding up oscillator simulation. |

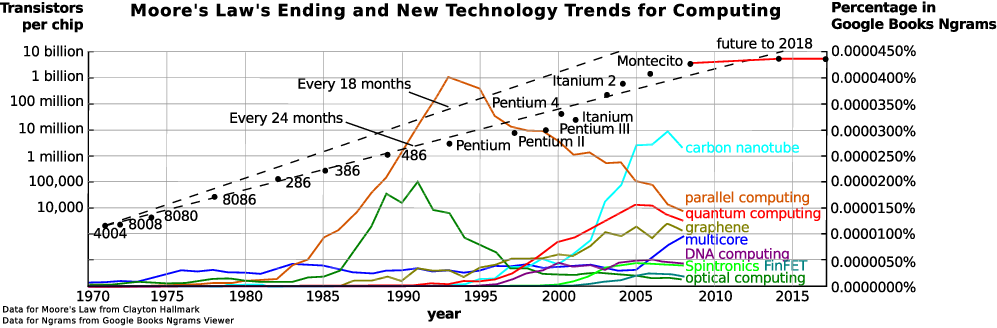

At the end, here is a graph showing the slowdown of Moore's Law, as well as several technology trends for computing with their "hotness" over time, measured by N-gram data from Google Books. I believe that the exploration of any of them, be it graphene or CNT, spintronics or silicon photonics, cannot thrive without an integration of knowledge from devices modelling, simulation algorithms and system-level design. And it is in these areas where I plan to continue my research.

|